Brian Bailie, Syracuse University

Abstract

How do we understand acts of protest using social networking technology as their respective starting points, and the temporary groups formed in these moments of tech orchestrated protest? How do the antithetical rhetorical acts of the corporations that market these technologies help create a context (scene) where these temporary groups are continually interpreted as unimportant? To answer these questions, I plan to give a brief description of “smart mobs,” and then discuss how a small, recent smart mob used technology to its advantage. To demonstrate how technology is the correct and appropriate channel for these types of protest groups as they try to attain their goals, I place this smart mob in Burke’s pentad, and at the same time, show how the larger societal belief in technology as a magic fetish object hinders a straightforward act of communicating discontent. To demonstrate the hurdles a smart mob must overcome to be taken seriously, I also place the antithesis of the smart mob, the corporation, into its own pentad. Then, through the use of this pentad, I show how my representative smart mob’s attempt at protest is complicated by the digital scene created by corporations—a scene which follows the archetypical narrative of technology as only a boon to the social status quo and corporate capitalism.Introduction

THE ACADEMY (AND OUR DISCIPLINE) has a love for grand figures. Any type of work with social movements is often seen through and discussed in terms of leaders who are easy to identify, and therefore, easily work as metonymic figureheads for their respective organizations. The speaker in this situation becomes the embodiment of the social movement, and s/he (and the organization s/he represents) is judged by hir ability to speak in accordance with the classic concepts of oratorical performance. Inevitably, this model conjures up images of a leader crafting an oration for public consumption in an offstage space; some text carefully crafted by the individual speaker working alone until the appropriate time of its release. It is easy to imagine all rhetoric, and especially unorthodox or polemic rhetorics, working in this way since it is comforting—it allows rhetoricians to make the unfamiliar familiar by pressing unusual or discomforting rhetorics into a Quintilian-like model of public performance.

This “Quintilian-like model of public performance” also extends to the hypothetical developmental models for protest rhetorics. The persuasive strategies of protest groups is often seen like the building of cathedrals, that is, “carefully crafted by individual [rhetors] working in splendid isolation” with no written statement or elocutionary act “released [or performed] before its time” (Raymond 2-3). While the cathedral style of building suasive strategies may be true for established groups (e.g. NOW, the NAACP, or Greenpeace), this is not the way many protest groups utilizing network technologies are being organized. The creation of the rhetorical strategies for these social movements are much more like a public market, where everything is “open to the point of promiscuity” and there can be “no quiet, reverent cathedral-building” (Raymond 3) since these protest groups coalesce and work like ribosomal sects—not a monolithic group—around a predetermined event which may or may not be related to a larger common cause. This means the rhetors making things happen are part of “a great babbling bazaar of differing agendas and approaches…out of which a coherent and stable system” emerges for finite amount of time (Raymond 3).

This is difficult for many in the American academy to conceptualize, let alone believe in, because it is contrary to how technology is taken up in the United States. As Cynthia Selfe explains in “Lest We Think the Revolution is a Revolution”:

we find ourselves, as a culture, ill equipped to cope with the changes that the “global village” story necessitates, unable, even, to imagine collectively ways of relating to the world outside our previous historical and cultural experiences. As a result...we revise the script of the narrative to fit within historically determined contexts that are familiar and comfortable. In doing so, we also limit our cultural vision of the technology changes that are acceptable and possible for us as a culture. (294-295)

Instead of seeing technology as something that can bring about social change, the dominant archetypical narrative is the continuation of capitalism into a new electronic frontier. While this can be seen as a trifling issue (Who cares if not everyone understands how new fangled electronics are being put to use?! It’s the end result for the group in question!) I argue that it is quite debilitating for organic protest groups when their method of organizing (new fangled electronics) is fore-grounded over their message of discontent. Groups/individuals that do not have the cultural capital of NOW or the NAACP use technology to create social networks and recruit people to their cause; if and when these groups are able to attain media attention it is counterproductive to their goals when the press presents them as a novelty act which used technology in an interesting way instead of a group advocating for change. In this situation, the fore-grounding of how the group mobilized to protest becomes an impediment for the protest group since the audience receiving this type of portrayal takes them up as an anomaly, as a group using flashy gadgets with no valid social message. Through using the work of Kenneth Burke it is possible to see how and why this belittling occurs, and at the same time, demonstrate how these emerging protest rhetorics utilizing technology are legitimate persuasive strategies for organic movements looking to create social change.

This may seem a bit dramatic. Still, rhetoric (to paraphrase Victor Villanueva) is the purposeful use of language and the way we construct/navigate our shared experiential reality, and because of this there are weighty penalties for the continued misnaming and misinterpretation of these rhetorical acts. With this in mind, here’s the question I pose for readers (and myself) to grapple with through the lifespan of this text: How do we understand rhetorical acts of resistance using technology enacted by these emerging protest groups (which from here on out I’ll call, to borrow the phrase from Howard Rheingold, “smart mobs”), and how do the antithetical rhetorical acts of the corporations that market these technologies help create a context (scene) where these groups are continually interpreted as unimportant?

To answer these questions, I plan to give a brief description of how smart mobs work and then discuss how a small, recent smart mob used technology to communicate their discontent to the larger world. To demonstrate how technology is the correct and appropriate channel for this group’s goals, I place this smart mob in Burke’s pentad, and at the same time, show how the larger societal belief in technology as a magic fetish object hinders a straightforward act of communicating discontent. To demonstrate the hurdles a smart mob must overcome to be taken seriously, I also place the antithesis of the smart mob, the corporation, into its own pentad. Then, through the use of this pentad, I show how the representative smart mob’s attempt at protest is complicated by the digital scene created by corporations—a scene which follows the archetypical narrative of technology as a boon to the social status quo and corporate capitalism.

Unpacking

The use of technology is often divided along socio-economic lines, and any use of technology is usually state-supportive in the most direct and circuitous ways. If we consider the history of the Internet, the World Wide Web, and the Web’s rise to the status of national treasure through its ability to be used as an electronic shopping mall, then we can see Selfe’s above quoted criticism as exceptionally erudite. Even more fruitful is placing Selfe’s “comfortable” technology claim into Burke’s description of ultimate hierarchies. In Burke’s ultimate hierarchy, the cultural narrative of “comfortable” technology is merely conforming to a rhetorical framework using capitalism as the “‘guiding idea’ or ‘unitary principle’” (A Rhetoric of Motives 187) of capitalism.

In capitalism, technology is considered one voice within a “diversity of voices,” one that like all the other voices within this social-political system are not “disrelated competitors that can work together only by the ‘mild demoralitzation’ of sheer compromise” but is interpellated to be one voice that represents “successive positions or moments in a single process” (A Rhetoric of Motives 187) towards building a paradise of never-ending, always increasing profits. In this milieu, technology is constructed as either a set of tools to open new markets and increase spending by consumers (the Web), or a way to defend and safeguard the social and political status quo needed to conduct business (the Internet’s origin as a part of a missile defense system built by the US Department of Defense.)

The normalcy of this situation is now being challenged through smart mobs, a congregation of protesters which lasts for an indeterminate (usually finite) amount of time and with the express purpose of demonstrating against a specific, group defined wrong. A smart mob comes into being by accessing the existing network of communication technology via their computers, cell phones, and traditional phones.Whereas this may not seem very edgy, it is when it becomes apparent these groups do this by using the grids of communication created with the intention of being state-supportive and a boon to corporate capitalism—not a “phone tree” to connect individuals whose interests may counter the corporations who built these networks, or challenge the national/state/local governments who equate the well-being of these corporations with their own well-being. In using these pre-existing, well-maintained communication networks, the smart mob is not only cost-effective and time efficient, but moreover, difficult for authority figures to sabotage since it “consist[s] of people who are able to act in concert even if they don’t know each other” (Rheingold xii, emphasis mine).

To demonstrate how a smart mob works, I will discuss the recent “Penny Prank” at Readington Middle School (hitherto referred to as the “small, recent smart mob”), place this smart mob into a pentad of its own, and in an effort to make clear how corporations naturally counter the utilization of technology for social change, also place the Nokia Corporation into a second pentad. By using the scene-act and the scene-agent ratios, I endeavor to make plain that “the nature of acts and agents [is] consistent with the nature of the scene” (here, the time periods and the experiential reality of both groups involved); that there is a direct relation between each group’s agency and their scene, i.e., their respective material, social realities; and the strategic modification of their respective scenes completely contains “the qualities” of their respective acts (Burke 1302, 1307). Through using Burke’s pentad I assert it is possible to see how messages using the medium of technology—while still emerging—is still a straightforward message; the message is just garbled due to the stranglehold that commerce has on the public’s imagination when it comes to the use of technology as a viable genre for communication. What needs to happen is a reconsideration of how we, as a culture, view technology and its uses, and a more realistic interpretation of computers, the Internet, cell phones, and the World Wide Web as everyday tools—not fetish objects imbued with a mystical quality. In showing two very dissimilar agents I hope to make plain how the Readington students and their action is just as normal—if not more so—than the aims of a corporate giant like Nokia.

The Scene-Act Ratio at Readington Middle School

Burke explains that in the scene-act ratio, “there is implicit in the quality of a scene the quality of the action that is to take place within it. This would be another way of saying that the act will be consistent with the scene” (1304). At Readington Middle School the students complained of being hurtled through their lunch period through the technologies of observation and the corresponding physical architecture of the school layout. They were lined up, kept in plain view, and then monitored and timed as they ate lunch. When the lunch period was up they were informed, most likely by a bell and the commands of school personnel, to return to their respective classrooms. That 250 students could purchase lunch, find a place to sit, eat, and clean up in 20 minutes is absurd; to point out this absurdity which was within the legal limits of good practices, they returned the favor to the school through their act of resistance. This act was the paying for lunch in pennies.

Lunch at Readington Middle School, at the time, cost two dollars, and therefore, the students politely rebelled against their schoolmasters by giving the cafeteria cashier exactly 200 pennies. (“Politely,” denotes the fact that pennies are still legal currency in the United States, so it is not a crime, that is, impolite or criminal, to pay for goods or services completely in pennies.) Because of this savvy protest move, when the lunch period ended the school staff was hard pressed to force the students back to classes since several of the students had not eaten. This conflict between the staff’s obligation to ensure the proper nutrition and their need to herd the students back into the educational work routine forced a managerial paralysis, and the students gave their intimated displeasure a material, physical presence through a work stoppage.

Within the confines of Readington Middle School, the act completely matches the scene; according to Michel Foucault schools based on the Western European model have a long tradition of being places of control and discipline. In this space of control and discipline techniques were developed that garnered the most out of individual student bodies, and everything was run with efficiency in mind. Early schools, Foucault explains, where built with the idea of using “few words, no explanation, a total silence interrupted only by signals—bells, clapping of hands, gestures, a mere glance from a teacher...Even verbal orders were to function as elements of signalization” (Foucault 166, 167). Foucault continues on to explain that even the structure of schools and how that space was utilized was meant to train and coerce students:

For a long time this model of the camp or at least it’s underlying principle was found in urban development...hospitals, asylums, prisons, [and] schools...The old, traditional square plan was considerably refined in innumerable new projects. The geometry of paths, the number of and distribution of the tents [here think classrooms and cafeterias], the orientation of their entrances, the disposition of files and ranks [here think halls and corridors] were exactly defined; the network of gazes that supervised one another was laid down. (171)Through this architecture Readington Middle School should have provided “a hold on [the] conduct” (Foucault 172) of the Readington 25 and their classmates, and with these years of bio-manipulation made (literally) concrete, alter the students through their educational regime.

The Readington 25, due to years within in the public education system, knew this system existed (even if they didn’t articulate it), and created the resistance that would be most effective in forcing that technology and architecture to break down: using the individual body as a site of disruption. By literally clogging the system with their individual bodies and ensuring that no body flowed smoothly through the cafeteria that day, the confines of the system swelled beyond its capacity and burst. While the previous metaphor likens the student bodies to water, the real action here was not bodies bursting out of the building but the introduction of entropy through a strategic use of a common action in that system, i.e., the method of payment. The disciplinarian system could continue to monitor and keep the students’ bodies in line (literally and metaphorically), but it could not work upon their bodies efficiently so as to make certain their movement through this part of the daily schedule was within the prescribed time limit.

To achieve this seditious, scandalous, and smart moment of civil disobedience, the students utilized the mundane technology available to them. Students used cellular phones, email, personal websites, blogs, and the traditional telephone to organize. In doing this they displayed how the smart mob method is an amazing moment of solidarity not built on a unified agenda or identity, but a temporary solidarity built around a common cause—their displeasure with the length of their lunch period. That this could occur at a school, where hetero-normative, consumer-capitalist identity and hierarchy is enforced by school personnel as a way to prepare students for their lives as adults, and also where the students self-police and maintain an organic rigid social hierarchy of groups based on race, ethnicity, socio-economic class, gender, sexual preference, academic track, affiliation with school extracurricular activity/sports participation and beauty standards (yes this is long, but it’s meant to be) displays the awesome power of the smart mob as an organizing tool.

The ability to organize around the act of composition (composing texts to inform) and the rhetoric of a specific cause (the disliked short lunch period) cut across a highly stratified caste system to unite them for one specific purpose. The act matches the scene as the school uses the physical layout of buildings, the use of lines (a “file” in Foucault’s military paradigm) a time schedule, and technology (to keep records, to schedule classes, to set-up the bell schedule, to store personal files, to record test scores), to act on the students. The students, in turn, used the layout of the building, being forced to stand in line, the time schedule, and technology (cell phones, the telephone, blogs, websites, email, and text messages) to resist.

The Scene-Agent Ratio at Readington Middle School

Placing the Readington Middle School rebellion within the scene-agent ratio explains why the students chose to use technology to organize, and how they decided on a work stoppage as the built- in swarming method inherent in the cafeteria architecture (swarming is the term often applied to the disruptive action of bringing an inordinate number of bodies to bear on a designated space to disrupt the everyday actions of daily living as a sign of protest). Burke asserts that in the scene-agent ratio:

[t]he correlation between the quality of the country and the quality of its inhabitants...by the logic of the scene-agent ratio, if the scene is supernatural in quality, the agent contained by this scene will partake of the same supernatural quality. And so, spontaneously, purely by being the kind of agent that is at one with this kind of scene the child is ‘divine’. The contents of the divine container will synecdochically share in its divine. (1305)Essentially, the agents will take on the qualities of their environment and use the tools and practices (agency) common to their scene. This group of agents used the architecture of the dining area and the technology of the Internet against the school, the two aspects that the school is par excellence in using as a way to coerce and manage the student body.

To create this protest, the students at Readington Middle School organized using “text messages, online blogs, and the good old fashioned telephone line” (<http://abclocal.go.com/wabc/story?section=news/local&id=5989226#bodyText> ), which actually matches the district’s action plan to “[a]ssess student skills on a continuous basis at the 3rd, 5th, and 8th grade levels and develop programs with curricula that fosters computer, communication, presentation, and design technology literacy skills” (“Readington Five Year Technology Plan” 5). The standards of behavior for the cafeteria state “All RMS students are expected to enter and leave the cafeteria in an orderly manner and to follow the lunchroom procedures set forth by the supervisors” (“RMS Student Handbook” 4), which they were in compliance with, and the students by paying with pennies (which there is no mention of in the student handbook) did not violate any of the prescribed standards for behavior in the student handbook dealing with cafeteria decorum. This challenge to authority is a subversion of the status quo in a public space in which the technologies of the ruling class were used against said class.

Nokia in the Scene-Act Ratio

That a discursive space dominated by the bourgeoisie, as described by Jürgen Habermas in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere still exists is demonstrated, I submit, by looking at the actions and strategies of a large, multinational corporation. In this case it is Nokia, a major player in most of the world when it comes to cell phone technology.

In the scene of hyper-competitive global capitalism, Nokia is making moves that will help it maintain its market share in the cell phone industry. As Lillie points out in “Cultural Access, Participation, and Citizenship in the Emerging Consumer-Network Society,” Nokia is pursuing strategies that promote mobile phones and other mobile information and communication technologies (MICTs) that “reduce the user’s ability to interact and effect change in the world” (41).

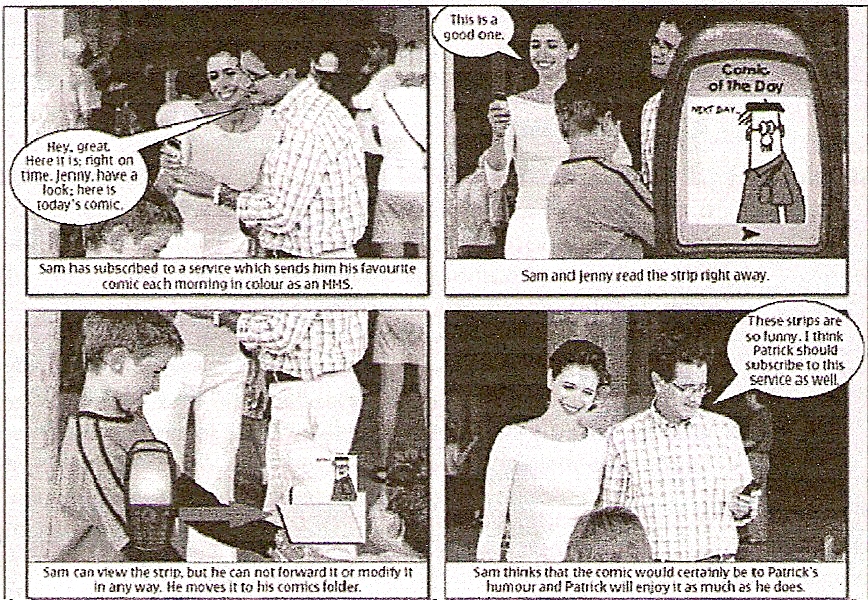

The company’s strategy involves Digital Rights Management (DRM), which works in a few key ways. First, as Lillie points out with the Nokia advertisement concerning subscription service (figure one), owners of Nokia handsets must sign up and pay a subscription fee to access the content they wish to see (I would also add that I have the sneaking suspicion the content available is limited, ergo, not offering much of a real choice in comparison to non Nokia services like YouTube, which is also limited due to copyright. This leads into, and possibly serves as another discussion, about the illusionary “freedom of choice” concept when only a finite number of choices are offered). When “Sam,” the fictional user in the advertisement, thinks his friend “Patrick” would like the comic, too, “Sam” can not just forward the comic onto “Patrick” since “MMS [Multimedia Message Service] has forward lock DRM embedded” (Lillie 42).

Fig. 1. First comic from the DRM White Paper. From Jonathan Lillie, “Cultural Access, Participation, and Citizenship in the Emerging Consumer-Network Society” (42).

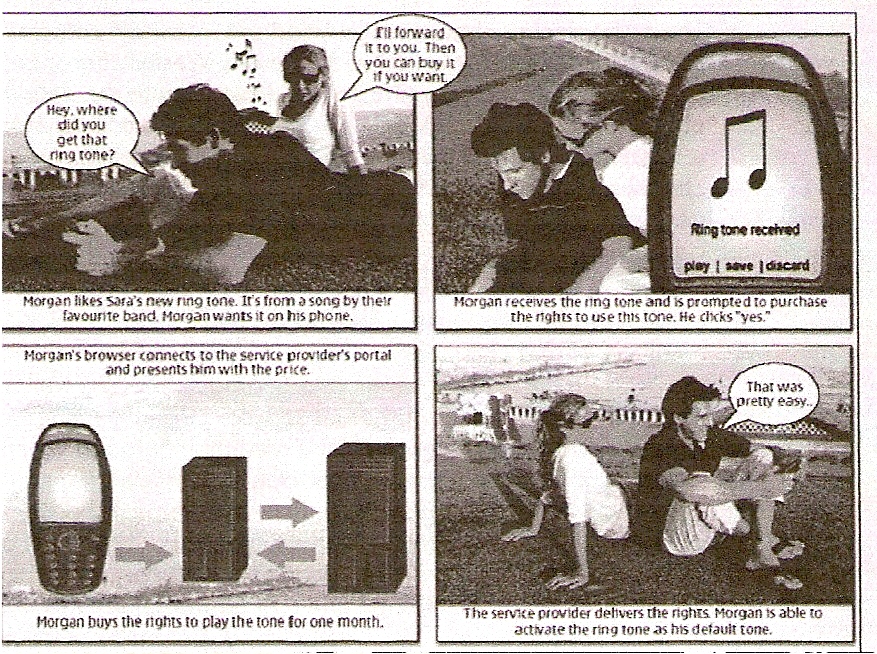

A similar thing occurs within the second comic (see figure 2), where “Morgan” likes the ringtone on “Sara’s” phone, which is a song clip from “their favourite [sic] band” (Lillie 42). “Sara” can not just send it to “Morgan” because he has a “Separate Delivery DRM” (Lillie 42) service. Because of this, “Morgan” will have to “buy the ‘rights’ to use it for a month, from the content provider from whom Sara got it” (Lillie 42).

Fig.2. Second comic from the DRM White Paper. From Jonathan Lillie, “Cultural Access, Participation, and Citizenship in the Emerging Consumer-Network Society” (45).

Because of the scene (or environment, or milieu) of corporate, unchecked capitalism, this strategy, this act, makes sense—probably to everyone reading this text since we all live in the same scene. Still, the act in and of itself is problematic as it means specific traditions and ideals of a democratic republic are negated through these types of acts. How these acts are problematic and tie directly into smart mobs I’d like to discuss later, but for now the most important concept to hold onto is what this type of socially approved act means. Lillie explains:

[Nokia’s advertisements which were a suasive artifact housed in the] DRM White Paper applies a notion of rights divorced from political or democratic theory and legal definitions of citizen’s human rights in its attempt...to control how certain digital cultural texts can be used. The rights of the citizens are essentially reversed in the discourse of DRM. Rights are not understood as guarantees of human liberty from specific modes of oppression, but are instead rules for how citizens can act in specific dealings with cultural texts. Corporations, rather than the state, are represented as being justified in appropriating and using the power to specify exactly what these rights are. The rights of the corporate citizen emerge as pre-eminent. (43)The “corporate citizen” mentioned in the above bloc text signifies the corporation as political citizens, as members who have the rights and privileges of an individual political citizen; this act is a conflation of the bourgeois who make up the boards and shareholders of Nokia and the company known as “Nokia.” Corporations are a specific legal, mass identity that allows individual members distance from the entity known as “Nokia,” i.e., so if Nokia, the company, fails, its assets, earnings, and holdings are liquidated to pay off creditors, and not the assets, earnings, and holdings of individual board members and shareholders who plan Nokia’s strategies and profit from Nokia’s performance. This fanciful display of mental gymnastics—an act which flies in the face of legal definitions, defined consequences for bankruptcy, and a categorization designed to hedge the risks for capitalists so as to encourage the investment of their wealth in the open market—to make Nokia a political citizen is enabled purely by the scene of global capitalism. Again, how corporations tie into smart mobs (even the little one of 25 students at Readington Middle School) will be taken up later.

Nokia in the Scene-Agent Ratio

As stated earlier in the paper, “by the logic of the of the scene-agent ratio, if the scene is supernatural in quality, the agent contained by this scene will partake of the same supernatural quality” (Burke 1305). In short, the character of the agent within the scene is a direct reflection of the scene, and if Nokia where an individual character in a “brutalizing” situation (scene), then Nokia would be a “brutalized” character as the “dialectical counterpart” (Burke 1306). And, as stated before, the agents will take on the qualities of their environment and use the tools and practices (agency) common to their scene. In this case, Nokia is a mass agent that uses the architecture of mobile networks and mobile information and communication technologies to turn a profit from the masses (purpose).

The Big Picture

Burke explains the overall framework for the grammar of motives in these terms:

The hero (agent) with the help of a friend (coagent) outwits the villain (counteragent) by using a file (agency) that enables him [sic] to break his bonds (act) in order to escape (purpose) from the room where he has been confined (scene). (1301)So, if we place the school smart mob into this setting, we get the Readington 25 (agent) outwits the school (counteragent) by using architecture and technology (agency) that enables them to shut down the operations of school lunch (act) in an effort to protest the unusually short lunch period (purpose) at their local public school (scene). In the case of Nokia, we see Nokia (agent) sidestepping traditional civil society (counteragent) by using the architecture created by mobile technology (agency) that enables them to control cultural texts (act) in order to turn a profit (purpose) within a public sphere dominated by capitalists (scene).

Now, the easiest move here would be to connect the situation of Readington Middle School and its reaction to the Readington smart mob to Nokia and corporate capitalism. I could say that the school is an agent, within a specific scene, whose action matches the scene (postindustrial nation in late stage capitalism which values docile workers) and their agency (detention) is a way to silence dissent (act) in order to keep the calm status quo of a typical, culturally appropriate school day (purpose). While I do think that’s true as a way to describe the motivation of the school, the larger question for me is how and why the Readington smart mob’s action has been taken up as a “prank,” and why the event put on by the smart mob is not known as the “Readington Lunch Protest” but as the “Penny Prank.”

Using Burke’s grammar of motivates, I have endeavored to make clear how two different entities describe our current shared political milieu (or scene), and using Habermas’ ideas concerning the public sphere, demonstrate how Nokia and its motivation matches, in spirit and intention, the current social scene of global capitalism. In the converse, I placed the Readington 25 into the same set of ratios to show how their motivation differs, and yet their scene, act, and agency match that of Nokia’s. Here, I’m pointing towards the differences in how each act is taken up, and how symbol using through the act of composition and the rhetoric that accompanies it are interpolated by wider society. So, let’s play with a simile. If we think of both Nokia and the Readintgton 25 as two trains, using the same methods, i.e., the technology of steam, and the same architecture of railroad tracks, how is it the Readington train is seen as less important than the Nokia train? Why is the Readington act described as a prank and the Nokia act seen as serious and ethical?

The point of using trains is to create the mental image of trains traveling on railroad tracks. These trains run parallel to each other for most of the time, but in specific ways they affect one another since one can effect the other’s schedule; what one carries can be transferred over to the other; when one is derailed it effects when and how the other is allowed back onto the network of railroad tracks.

Essentially, this attempt at a railroad inspired metaphor is an attempt to a make point: Nokia does not directly influence the Readington 25, but Nokia’s acts within the world scene affect the Readington 25. How Nokia deals with symbols and cultural texts decides how the Readington 25’s act is taken up by society, and in actuality, all smart mobs and their actions.

George Myerson argues:

The mobilising [sic] of communication turns out to be the precursor, the necessary precondition, for this larger mobilisation [sic] of the everyday. The ‘m’ [in MICTs] will stand for a new order of every day life: faster, neater, sharper...There will, if the ‘m’ is the future, be no idea of communication distinct from the idea of commerce. To communicate will mean the same things as to exchange money. The two activities will simply be merged. (qtd. in Lillie 44).And here, in the United States, I argue this has occurred. Money and communication, the ability to access information through a library, listen to a song from iTunes, or share images over long distances have all followed the Nokia model. Everything must be paid for, and paid for each time it is used or paid for on a regulated, monthly schedule. No cultural artifact can be claimed as something political citizens have the right to access by virtue of being a member of said society; they must pay for each piece of text they want to share within the larger discourse community that forms the US.

This may seem frivolous. It may be countered by explaining if a person does not want to pay, then the person does not have to sign up for services. Still, the talk either for or against the Nokia model dominates the ways of knowing, being, and describing our culture’s experiences when it comes to dealing with technology. In connection to the Readington 25, no one in the mainstream media can properly name the actions of the students since it does not fit a commerce model. Instead of being described as a “protest” an “uprising” or a “smart mob” it’s called a “prank” because it does not, to paraphrase Myerson, treat communication as money.

Through a scene empathetic to capitalism, even dominated by capitalism, the idea of the smart mob, its use of technology, and what it can accomplish as interpreted merely as a group of malcontents glomming together through sheer luck of the encounter, or worse, a prank played by school children. The smart mob is a perversion of the public sphere model as described by Habermas, and is even a perversion of the public sphere proposed by telecommunication giants, but it is a quiet perversion which exists in an underworld state since it, and its motives, can not be recognized in the current social-political milieu (scene).

What Does This Mean for Rhetoric?

Cynthia Selfe in “Lest We Think the Revolution is a Revolution” confronts this issue of technology and social change by analyzing a number of advertisements selling technology through a narrative in which we “create a global village in which the peoples of the world are all connected—communicating with one another and cooperating for the commonweal” (294). And with the situation in Readington, this would seem to be the case. A group of young, educated American children practiced the time honored American tradition of civil disobedience. They saw a situation which they felt violated the common happiness and well-being of all the students, and therefore, communicated with one another and cooperated in a way to highlight the grievous situation and, hopefully, force some type of change. Instead, they received detention (two sessions in fact) and have had their act (which in the United States should remind people of the old patriotic stories concerning the Boston Tea Party and the American Revolution) degraded to a prank. Why?

As Selfe demonstrates with “Lest We Think...” technology in and of itself is a business. All the advertisements Selfe shares with readers are notices for products to buy which will enhance a user’s time with her technology. As Ziauddin Sardar points out the privatized and deregulated frontier of “cyberspace has done much to boost business—trade is growing twice as fast, and foreign direct investment four times as fast, as national economies” (22). This is the dream world of corporations like Nokia and governments who run societies in which both the governing body and the masses see themselves as obligated to being amenable to laissez-faire capitalism (the United States, for example).

With this in mind, I assert that this cultural narrative where technology is a tool of capitalism there is only one acceptable roles available to individuals: consumer. In a situation where people band together and try utilizing technology for social change, they will be thwarted because the audience, or to borrow from Mikhail Bakhtin, addressees, will never match the imagined ideal addressee, that is, the superaddresse. Technology, in this setting, creates disempowering social roles which make “change hard to imagine and even harder to enact”—specifically because “technology is involved” (Selfe 316). If the message (“purpose” in the pentad) of an act (in the pentad sense) does not match the narratives saturating technology (technology would be “agency” within Burke’s nomenclature), then the message will be disregarded, or worse, misinterpreted and misnamed.

This misinterpretation and misnaming occurred with the Readington 25. Their act of protest, instead of being read as an act peaceably challenging the rules of their immediate environment (scene), was read as a “prank” and can be found on YouTube using the delimiters “penny” and “prank.” The entire newscast I’ve used as the artifact for analysis refers, constantly, to the students’ actions as a clever trick because it used things like the web, the Internet, and text messaging. In the actual footage form the interview, it isn’t mentioned until the very end—literally the last few seconds—students are upset by the conditions and rules they’re living under when it comes to their lunch period. The entire segment focuses on the novel use of the technology often used for business or consuming, and the administrators interviewed see it as an embarrassing, harmless, and punishable offense. The administrators make no mention of considering a change, nor do they acknowledge the students may be trying to send a message.

For rhetoric, this means two things. First, and despite recent criticisms that he is obtuse, Burke’s ideas are found to exist in experiential reality. The students who formed the Readington 25 were agents who imagined their message would be heard and understood by someone within the school administration, and using the elements of rhetoric Burke delineates, thought they were making a message with communicative value using the agency available to them in their immediate scene. Second, technology, while it may seem old hat in the brave new world of the 21st century, still causes new issues and concerns for rhetors. Simply put, technology and its accompanying, special narratives and rhetorics problematize Burke’s pentad; but this is due to audience expectation and their terminsitic screens—not the smart mobs nor its methods, nor due to a flaw in Burke’s theories.

Using Burke once again, a motive behind this audience expectation may be discernable by applying his concept of “god-terms” (276, A Rhetoric of Motives). The administrators may not consider making changes to the lunch period since the baggage with the signifier “technology” is on the level of a vague, “ultimate” (188, A Rhetoric of Motives) term which the administrators are expected to make sacrifices for within the cultural-linguistic system they exist in. As I demonstrated earlier in this paper with the Nokia example, the system these administrators live in is a capitalistic hierarchy, one where technology furthers the agenda of global capitalism. Anything that does not meet this standard is filtered through the terministic screen created by this ultimate term and left on the mediatory ground as useless slag. Second, using this idea that technology is somehow involved in an “ultimate transcendence” (276, A Rhetoric of Motives) explains the mystification that occurs whenever technology is invoked in mundane talk—meaning that oftentimes the mystery of caste is in play when technology is the subject of discussion. In a caste system where technology is often seen as the channel to US economic and military domination, “[i]t is the ‘glamour’ of caste alone that makes [the everyday citizen] ready to subordinate his will to the will of the institution[s]” (211, A Rhetoric of Motives) that govern American society. This “glamour,” I propose, also coerces everyday people and media pundits into denying the possibilities technology holds outside the uses prescribed by the American ruling class. This, in turn, means anything not fitting within this hierarchy of terms, like smart mobs, are often overlooked, misnamed, and misinterpreted.

This expectation of “ultimate transcendence” is due to the rhetorics surrounding technology. As Sardar points out in “alt.civilizations.faq: Cyberspace as the Darker Side of the West,” cyberspace (his term for what I’ve referred to until here as either the Internet or the World Wide Web) is seen as the “new frontier” (21). In this new frontier the “desire of the settlers [is] for absolute freedom” and “new spaces to conquer” (16) all the while making at tidy profit (the Nokia example, Selfe’s critique, Sardar’s figures all previously alluded to in this paper).

Sardar asserts this is continuation of the Utopian drive first started by Europeans like Sir Thomas Moore and Francis Bacon, and in fact, the technologies that make the Internet, text messaging, and the World Wide Web possible are nothing more than a “designer techno Utopia” that “delivers what capitalism has always promised: a world where everything is nothing more than the total embodiment of one’s reflected desires,” and that space serves as an escape for people because “morality and politics [have] become meaningless, [because] social, cultural, and environmental problems seem totally insurmountable...the seduction of the magical power of technology [has] become all embracing” (34).

This rhetoric means that any symbol manipulation or communication, or action produced by the inhabitants of said world, e.g., the Readington 25, can not be seen for its intended purpose because it does not fit the rhetorical schemes commonplace to the mainstream’s take on technology. If we continue in the current mode of thinking described by Burke and Sardar above, then all things produced within the confines of the term “technology” will always be misnamed and misinterpreted. How do we move past this, make meaning, and come to understand the ways that technology is being used by social movements?

Better Descriptions

One way for this to happen is better descriptions of smart mobs. A theoretical base that could provide a better, thicker description of what is actually happening in places like Readington is to start with Bakhtin’s views on the use of macaronic language. According to Bakhtin, in macaronic language situations “the languages that are crossed in it are relative to each other as do rejoinders in a dialogue; there is an argument between languages, an argument between styles of language” (76). This “argument” is more than argument in “the narrative” or “abstract” sense; this is “a dialogue between points of view, each with its own concrete language that can not be translated into the other” (76).

I propose this state of affairs existed in the Readington uprising, and in both technology and language worked in conjunction to create a moment of dialogic protest, and because of that the macaronic concept applies to language and technology. In Readington, both the state officials (the faculty and staff of the school) and the smart mob (the students) used technology, but the use of technology by the smart mob parodied the use by state officials. Instead of technology serving as an element of order in a larger architecture of panoptic surveillance, technology—in the hands of the Readington 25—created disorder since it was used to coordinate the disruption of normal routines.

The aspect of macaronic language Bakhtin points out, that the use of such language represents “a dialogue between points of view, each with its own concrete language that can not be translated into another” is the power and flaw of macaronic uses of language and technology. While in the short term the Readington 25’s methods were effective, their goals, and the methods used to try and achieve those goals, were ultimately distorted when presented to the larger audience of observers outside their immediate locale.

To combat this, the grand narratives of the individual hero creating ideologically pure protest groups needs to be suspended when dealing with moments of protest. The talk and writing that goes into the organizing either moments of, or groups devoted to, social protest need to be examined in a new way that discerns the difference between traditional methods of group creation and new, communication technology enabled methods. One way would be to combine Bakhtin’s idea of macaronic language and Burke’s pentad, as well as Burke’s concepts of hierarchy and god terms from A Rhetoric of Motives. Using Bakhtin’s idea of macaronic language will keep researchers aware of the possibilities that might be overlooked due to their immersion in the technophile milieu we currently traverse, and at the same time using Burke’s pentad, terms and hierarchies will allow researchers to subtract the obvious and keep the meaningful.

While this paper can not close with a definitive answer to the question: “How do we understand rhetorical acts of resistance using technology enacted by ‘smart mobs,’ and the antithetical rhetorical acts of the corporations that market those technologies?”, it can at least provide a starting point for a new type of work. An analysis of protest groups using the work of Burke and Bakhtin may allow for the correct naming and interpretation of rhetorical acts put forth by groups like the Readington smart mob. By applying the work of Burke and Bakhtin, it will be easier for scholars to provide a thick description of social movements as they actually exist, and not as they are imagined to be.

*Brian Bailie is a doctoral student in the Composition and Cultural Rhetoric Program at Syracuse University. He can be contacted at bjbailie@syr.edu

Works Cited

Bakhtin, Mikhail. “From the Prehistory of Novelistic Discourse.” The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin. Ed. Michael Holquist. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1984.

Burke, Kenneth. “From A Grammar of Motives.” The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present. 2nd ed. Eds. Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg. New York: St. Martin’s, 2001. 1298-1324.

--. A Rhetoric of Motives. Los Angeles: U of California P, 1950.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Random, 1976.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Trans. Thomas Burger. Cambridge: MIT P, 1991.

“Kids Get Detention for Penny Prank.” 7online.com. 6 May 2008. ABC inc. 21 Apr. 2008. <http:// abclocal.go.com/wabc/story?Section=news/local &id= 5989226#bodyText>

Lillie, Jonathan. “Cultural Access, Participation, and Citizenship in the Emerging Consumer-Network Society.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. 11.2 (2005): 41-48. Communications and Mass Media Complete. EBSCO. Syracuse U. Syracuse U Lib. Keyword: Flash Mobs. <http://search.ebscohost.com>. 4 Apr. 2008.

Raymond, Eric Steven. “The Cathedral and the Bazaar.” The Cathedral and the Bazaar. Ed. Eric Raymond. 20 Nov. 2006. 21 Mar. 2009. <http://www.catb.org/~esr/writings/cathedral-bazaar/>.

“Readington Five Year Technology Plan.” Readington Township Public Schools. Schoolwires. 18 Apr. 2008.<http://www.readington.k12.nj.us /771100726191951/site/default.asp?>.

Rheingold, Howard. Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution. Cambridge: Perseus Publishing, 2003.

“RMSSchoolHandbook.” Readington Township Public Schools. Schoolwires. 18 Apr. 2008. <http://www.readington.k12.nj.us/ 77111572720218/site/default.asp>.

Sardar, Ziauddin. “alt.civilizations.faq: Cyberspace as the Darker Side of the West.” Cyberfutures: Culture and Politics on the Information Superhighway. Ed. Ziauddin Sardar and Jerome R. Ravetz. New York: New York UP, 1996. 14-41.

Selfe, Cynthia. “Lest We Think the Revolution is a Revolution: Images of Technology and the Nature of Change.” Passions, Pedagogies, and 21st Century Technologies. Eds. Gail E. Hawisher, and Cynthia Selfe. Logan: Utah State UP, 1999. 292-322.